We have reached the 30th year of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. An increasing number of people of this generation either do not know or do not remember the earthquake. Now that the Nankai Trough earthquake is said to "could come at any time," it is a major mission of PACIFIC CONSULTANTS, which is involved in social infrastructure development, to pass on the memories of the earthquake and utilize them in disaster prevention, disaster mitigation, and BCPs. Managing Executive Officer, Mikiyo YAMADA, Director/Board Member, who was working at the Osaka Branch Office (now Osaka Headquarters) at the time of the earthquake, interviewed Shinichi KITADA of the Osaka Transportation Infrastructure Department's Earthquake Resistance Section, who was forced to live as an evacuee after the disaster in Kobe, while working on restoration and reconstruction.

<The Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake>

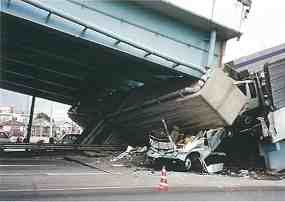

At 5:46 a.m. on January 17, 1995, a massive earthquake of magnitude 7.3 (Hyogo Prefecture's Southern Earthquake) occurred with its epicenter in the north of Awaji Island. A seismic intensity of 7 was observed in Takatori, Suto Ward, Ohashi, Nagata Ward, Ozeki, Hyogo Ward, Sannomiya, Chuo Ward, Rokkomichi, Nada Ward, Sumiyoshi, Higashinada Ward, the area around Ashiya Station in Ashiya City, a strip of land around Shukugawa in Nishinomiya City, parts of Takarazuka City, and parts of Kitadancho, Ichinomiyacho, and Tsunacho in the northeastern part of Awaji Island. Over 6,400 people were killed and over 40,000 were injured, and approximately 250,000 houses were completely or partially destroyed. There was also extensive damage to railways, roads, bridges, and port facilities, including the collapse and fall of viaducts on the Sanyo Shinkansen and several expressways, and the breaking of subway station pillars. This was the largest earthquake since the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923.

INDEX

- I never thought a major earthquake would occur in Kansai

- Establishment of the earthquake disaster reconstruction department

- Dynamic analysis for earthquake-resistant design

- Meeting the standards is not enough

- We must prepare for the Nankai Trough earthquake

I never thought a major earthquake would occur in Kansai

YAMADA: I'm originally from Kyoto, and after joining the company I worked in Osaka for a long time. KITADA-san was a senior colleague when I was in Osaka, and I think he came back from Tokyo when I was about 6 or 7 years into the company.

KITADA: I was born in Himeji and joined the company in 1973. I studied civil engineering, but I thought that working for a government office or as a general contractor was not quite what I wanted, and then my seminar teacher told me about the job of consultant engineer. I thought it would be interesting to work for a government office as a client and provide technology for infrastructure development, so I joined the company. After joining the company, I worked on designing roads and bridges, and was transferred to Tokyo once, but returned to Osaka to expand our business in western Japan and increase the number of staff.

YAMADA: Like me, people in the Kansai region never thought they'd experience a major earthquake.

KITADA: I never imagined it. My house is on the 11th floor of an apartment building in Hyogo Ward, Kobe City, and at first I heard a loud boom and wondered what it was, but the moment I did, I was hit by a violent tremor. Furniture fell over and the room was in such a mess that there was no room to stand. Luckily, my wife and three children were safe, but the building was dangerous so my family evacuated to the gymnasium of the elementary school next door. In some apartments the doors were warped and wouldn't open, so we helped residents get in through the windows and there was chaos. The apartment building was surrounded by old wooden houses, but I could see flames rising.

YAMADA: At the time, I was living in an apartment building in the suburbs of Kyoto, about 40km away from Kobe in a straight line, and although the shaking was quite strong, I never dreamed it would be such a big earthquake. I was shocked when I turned on the TV.

KITADA: Because it was an inland shallow-focus earthquake, it didn't spread very far.

YAMADA: That day at the office, we were quite worried because we couldn't get in touch with KITADA-san.

KITADA: I wanted to contact my company, but there were no cell phones at the time, and I had to rely on public phones, but because everyone was using them, the 10 yen coins had gotten stuck inside and they were unusable. It's really unsettling not being able to contact people. I was able to let them know that I was safe soon after, but my family and I had to live in a shelter for a while. It was cold.

YAMADA: The commutation must have been difficult, too, right?

KITADA: If I went to Ashiya, the trains were running from there. So I walked to Sannomiya, took a bus from Sannomiya to Ashiya, and then changed to the train from there. I continued like that for about two or three weeks, and then my company secured me a dormitory in Osaka. I lived there for about a month. Even so, I was worried about my home in Kobe, so I went back there frequently.

Establishment of the earthquake disaster reconstruction department

YAMADA: At the time of the earthquake, former chairman Hasegawa, who was then General Manager, Chugoku Branch Office came to Osaka for a meeting. There are many things that the company has worked on in Kobe. I joined the members and walked around various places to check the situation. I was surprised that the scenery changed completely after a 20-minute train ride, even though the city of Osaka was completely fine. After that, the company launched the Earthquake Reconstruction Department.

KITADA: When the immediate rebuilding of our lives was coming to an end, we gathered people from Tokyo and Osaka to form the group with the aim of prioritizing disaster recovery work. I think it was around mid-February. The group consisted of about 20 people, with two to four people assigned to each department of roads, rivers, structures, ports, planning, and ground. I was a member of the structures department, and we also had a specialist earthquake resistance engineer from Tokyo join us. The first thing we did was to investigate the damage situation related to infrastructure and assess the damage. Only through this assessment can we know the full extent of the damage, as well as the recovery methods and costs. After looking at this, the government will decide on priorities and take budgetary measures. Therefore, nothing can start unless this assessment is completed. We worked around the clock, working every day without sleep, but we felt that we had to do it.

YAMADA: Even so, it was truly a shock for us engineers to see the extent of the damage to civil engineering structures right before our eyes.

KITADA: We never imagined something like that would happen, like the site where 17 bridge piers on the Hanshin Expressway Route 3 Kobe Line collapsed together with their superstructures. Although it was not designed by our company, this bridge was an integrated structure of the upper girder and pier, known as a Pilz bridge, and was thought to be rather resistant to earthquakes. Other incidents included the buckling of steel piers on expressways and railways, collapse of bridges, and destruction of beams. It was said that underground structures would be safe because they would sway with the earthquake waves, but there was also major damage underground, such as the fracture of the central pillar of a subway box frame. In fact, the pedestrian deck in front of Ashiya Station, which I designed, moved in the earthquake, destroying part of the building.

Dynamic analysis for earthquake-resistant design

YAMADA: There were high expectations of PACIFIC CONSULTANTS when it came to recovery and reconstruction.

KITADA: I think so. In fact, we were commissioned to do a lot of earthquake-resistant design work for railways and roads. After the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, it became necessary to conduct dynamic analysis to see how structures would actually shake and ensure their earthquake resistance, but at the time, PACIFIC CONSULTANTS and a few other companies were the only ones who could do this. We designed Umihotaru on the Tokyo Bay Aqua-Line and other famous long bridges around the country, and I think people had high expectations of us because we had incorporated dynamic analysis from an early stage.

YAMADA: I think the experience of designing Metropolitan Expressway was also a big factor in improving our earthquake-resistant design technology. It was a very complicated project, like putting a bridge on top of another bridge. In the first place, the earthquake-resistant design standards for civil engineering structures before the earthquake were just a thin pamphlet-like book, and the calculation formulas were simple. It was enough to assume a horizontal force of about 20% more than the structure's own weight, and as long as it didn't break, it was fine. There was only a little bit of information in the appendix at the end of the book about how to do the calculations for complex structures. We realized that we couldn't design it that way, so we made our own efforts. I think that led to improving the theory of dynamic analysis and design methods.

Meeting the standards is not enough

YAMADA: Civil engineers need to keep in mind that even if a design is made according to guidelines and specifications, an unexpected disaster may occur and the bridge may be destroyed. It wasn't caused by an earthquake, but there was a time when a bridge over the sea that I designed collapsed due to waves. Of course, the design met the standards and there were no problems with the construction, but it was hit by what we would now call an unexpected wave. It was embarrassing. I made a mental note to never let the same thing happen again. Engineering calculations are important, but it's also important to have an engineer's sense of when a place might be dangerous, and I think it's important to hone that kind of intuition through various experiences.

KITADA: When I was young, we decided to build a road on the sea by filling in land and building a revetment, and I designed it so that soil would be placed between two sheet piles. A tie rod was used to pull the sheet piles so they wouldn't open up, but this broke. We had ensured that the tensile strength was within the standards, but we hadn't given enough consideration to the load of the soil on top. After that, I made it a point to not just check the standard values, but to question myself whether the design was really okay. If I was unsure, there were plenty of experienced seniors to ask.

YAMADA: I think it's important. Natural disasters are only getting more severe. Is it really okay to follow the prescribed design conditions? For example, the drainage capacity of a road is generally assumed to be about 80 mm of rainfall per hour. However, torrential rains exceeding 100 mm are not uncommon these days. If we over-specify, the client will warn us, but I think it's also necessary to make efforts to ensure that certain parts are stronger than the standards while avoiding cost increases.

We must prepare for the Nankai Trough earthquake

KITADA: As someone who was hit by an unexpected earthquake, I think we must be well prepared for the inevitable Nankai Trough earthquake, as the unexpected will always come. The Nankai Trough earthquake is particularly frightening due to the Tsunami, but we know that damage can be greatly reduced if people can evacuate quickly. We need to be properly prepared in terms of both hardware and software. To achieve this, I believe that the most important thing for infrastructure engineers is "passion." I think it is important to work with the desire to create something and to provide a more convenient and safer daily life.

YAMADA: It's true that engineers are based on solid basic knowledge and accumulated experience, but I want them to build their own unique thoughts from their successes and failures at work. Of course, there is a limit to what one person can experience, so I think we need to listen to the stories of our seniors and the valuable earthquake experience like Mr. KITADA's today, and provide a place for the company to pass these stories on to future generations, so that they become assets for each individual.

KITADA: As a consulting engineer for over 50 years since I joined the company, I have been able to pour my own thoughts into my work. This is because I have been a part of PACIFIC CONSULTANTS, a pioneering consulting company that is responsible for the development of social infrastructure and has earned the trust of society. I hope that all employees will take pride in their work and continue to contribute to the development of infrastructure both in Japan and overseas. Also, when the earthquake occurred, all employees donated money to those employees who were directly affected by the disaster as a sympathy for the damage. I would like to take this opportunity to express my belated gratitude. Thank you very much.